Across New York City, thousands of immigrants confront the same question every time they get sick: Where do I go for help? For many, the answer isn’t a hospital or urgent care center, but an organization that speaks their language — literally and culturally. Health Outreach to Immigrants, or HOI, was founded to make that bridge possible.

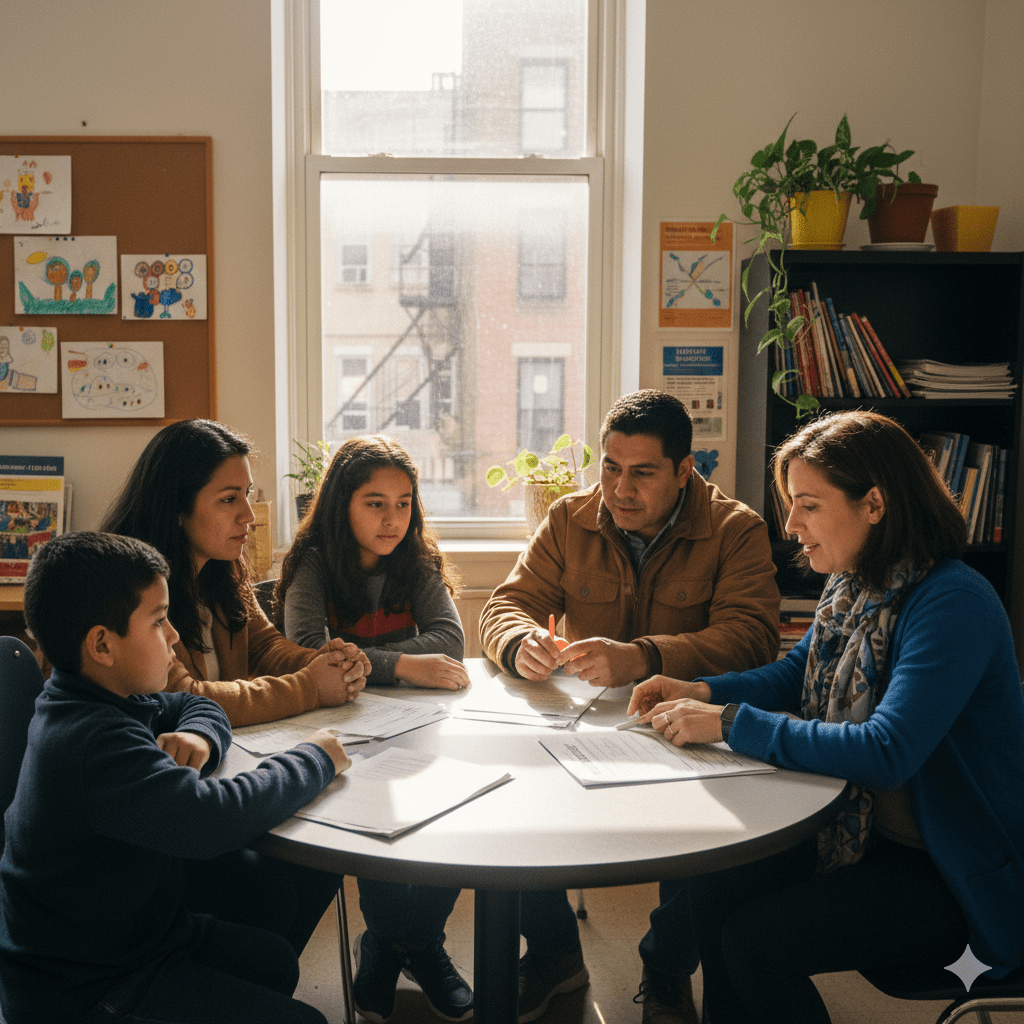

HOI’s work is grounded in direct advocacy. The organization focuses on helping immigrant families — many of them Spanish-speaking and uninsured — enroll in health coverage, find affordable clinics, and understand their rights as patients. In neighborhoods where poverty and language barriers often overlap, that access can determine whether a child receives preventive care or ends up in an emergency room.

What sets HOI apart is its on-the-ground approach. Staff and volunteers meet people where they already are: community centers, local churches, food pantries, and ESL programs. The goal isn’t just to hand out pamphlets; it’s to build trust. That human connection often makes the difference between a family avoiding care out of fear and one taking the first step toward treatment.

The organization’s outreach also reflects a larger truth about the city’s healthcare infrastructure — that formal systems often depend on informal ones to reach the most vulnerable. HOI collaborates with local clinics and hospitals to ensure immigrants can access services without discrimination or intimidation, particularly those navigating complex immigration statuses or limited English proficiency. By working in Spanish first, they meet patients not at the system’s front door but at its margins, helping them cross into spaces that once felt closed off.

Yet the work remains uphill. Even as state initiatives expand coverage, many immigrants still hesitate to seek care, worried that hospital visits could affect future immigration applications. Misinformation spreads quickly; clarity does not. That’s where HOI’s patient educators step in — explaining which programs are safe, what information clinics can request, and how to advocate for interpretation during appointments.

For New York’s immigrant communities, access isn’t abstract. It’s lived in daily acts of navigation — translating paperwork, asking questions, and daring to trust institutions again. HOI’s model acknowledges that reality. By pairing policy knowledge with human understanding, it offers something rare in healthcare: a system that listens before it instructs.

The story of HOI is, ultimately, the story of New York itself — layered, multilingual, and constantly evolving. In a city built by newcomers, the right to care in one’s own language is not a luxury. It’s recognition.